Databases often need to handle multiple people or processes accessing and modifying data at the same time. Without proper mechanisms, you can get race conditions, lost updates, or inconsistent data. PostgreSQL (and most relational databases) provide several ways to handle this.

We’ll cover pessimistic locks, optimistic locks, and database constraints, along with examples and caveats.

#Pessimistic Locking

Definition: Lock the row before modifying it to prevent other transactions from interfering.

Postgres assumes the worst — that conflicts will happen — so it locks proactively.

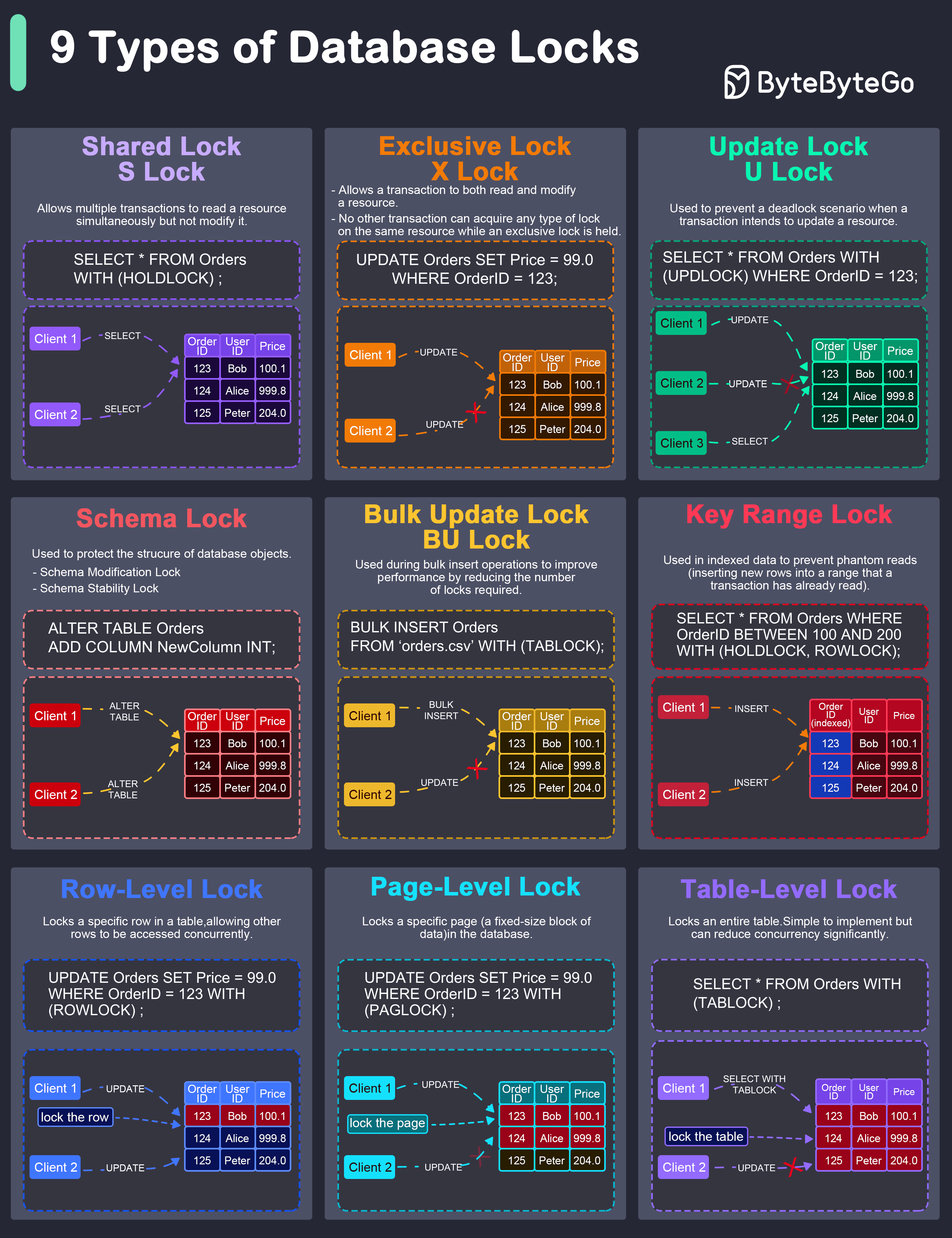

Common Types in PostgreSQL

| Lock | Description | Can update keys? | Blocks stronger locks? |

|------|------------|-----------------|-----------------------|

| FOR UPDATE | Full exclusive lock | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes |

| FOR NO KEY UPDATE | Weaker exclusive lock | ❌ No | ✅ Yes, but weaker locks allowed |

| FOR SHARE | Shared lock for reading | ❌ N/A | ✅ Blocks strong updates, allows concurrent reads/shares |

| FOR KEY SHARE | Protects foreign key references | ❌ N/A | ✅ Weakest lock |

Example: Bank Account

1-- Transaction 1

2BEGIN;

3SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE;

4UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = 1;

5COMMIT;

6

7-- Transaction 2 (concurrent)

8SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE; -- waits until T1 commits

9Explanation

- Transaction 2 is blocked until Transaction 1 commits.

- Safe for high-risk updates like money transfers.

Example: FOR NO KEY UPDATE vs FOR UPDATE

1-- Transaction 1

2BEGIN;

3SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 1 FOR NO KEY UPDATE;

4UPDATE users SET name = 'Alice' WHERE id = 1; -- ✅ allowed

5UPDATE users SET id = 2 WHERE id = 1; -- ❌ not allowed (key change)

6

7-- Transaction 2

8SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 1 FOR SHARE; -- ✅ allowed concurrently

9SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE; -- ⏳ waits

10Key takeaway:

- FOR NO KEY UPDATE is weaker — allows some concurrent reads/locks but still protects keys.

- FOR UPDATE is stronger — blocks all other modifying locks.

Pros:

- Prevents conflicting updates.

- Guarantees data consistency for critical rows.

Cons:

- Can block other transactions, causing wait times.

- Potential deadlocks if multiple transactions lock rows in different order.

- Reduces concurrency, especially in high-read environments.

Use cases: Banking, inventory stock updates, reservation systems.

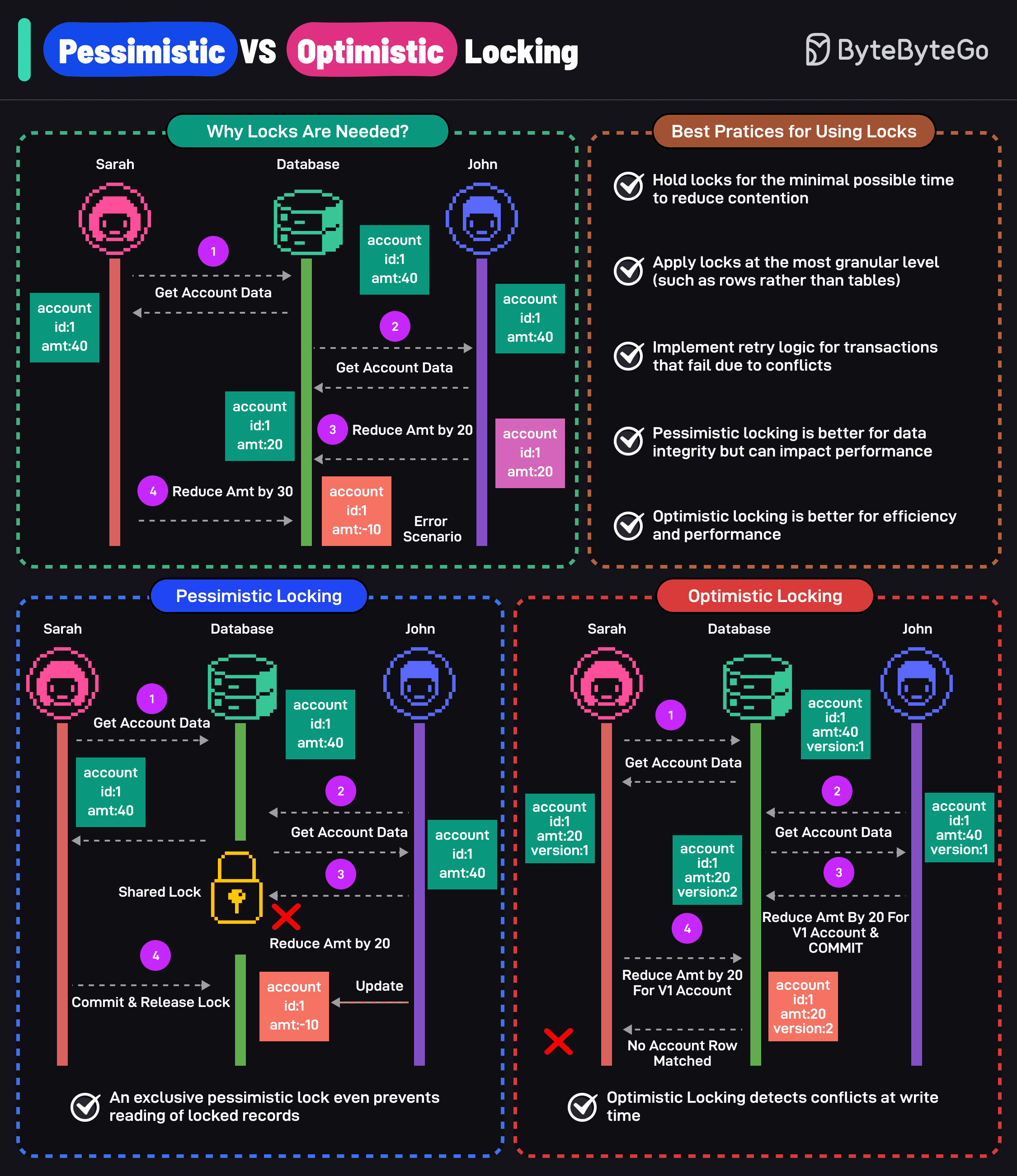

#Optimistic Locking

Definition: Assume conflicts are rare. Don’t lock rows; validate before committing. How it works:

- Read the data.

- Modify in memory.

- Check a version number or timestamp before commit.

- Retry if the version has changed.

1-- Table: accounts

2-- Columns: id, balance, version

3

4-- Transaction

5UPDATE accounts

6SET balance = balance - 50, version = version + 1

7WHERE id = 1 AND version = 3;

8If version changed since reading, the update fails → retry, allows high concurrency, especially in read-heavy systems.

Versioning Strategies

- Integer Version Column (Recommended)

- Increment a number every update.

- Safe and deterministic.

- Easy to implement and doesn’t depend on system time.

1UPDATE accounts

2SET balance = balance - 50, version = version + 1

3WHERE id = 1 AND version = 3;

4Timestamp / Datestamp Column

- Some developers use updated_at or last_modified to detect changes.

- Problem: If your system runs on multiple nodes or servers, clock skew may occur.

- Node A’s clock is slightly ahead of Node B.

- Updates may falsely fail or incorrectly succeed.

- Timestamps are not fully safe for optimistic locking in distributed systems.

Pros:

- No blocking for readers.

- High concurrency.

Cons:

- Retry logic needed.

- Not ideal for highly-contended rows.

Use cases: Dashboards, analytics, low-conflict transactional data.

Best Practice

- Prefer integer version numbers over timestamps.

- Combine with constraints to ensure data integrity.

- For distributed systems, avoid relying on system clocks for versioning.

#Database Constraints (Data-Constrained)

Definition: Use database rules to enforce valid data automatically.

Examples:

- CHECK(balance >= 0) → prevents negative balances.

- UNIQUE(email) → prevents duplicates.

- FOREIGN KEY → ensures relationships exist.

Race Condition Issue Example

1-- Balance: 100

2

3-- Transaction 1 reads balance = 100, plans to withdraw 80

4-- Transaction 2 reads balance = 100, plans to withdraw 50

5

6-- Without locking, both update → CHECK constraint may fail at commit

7Explanation : Constraints validate after the fact, not during the transaction.Race conditions are possible without additional lock

Safe Approach: Combine Constraints + Locks

1BEGIN;

2SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE; -- lock the row

3UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 80 WHERE id = 1;

4COMMIT;

5Now, concurrent transactions wait rather than risking invalid data

Pros:

- Automatic data integrity.

- Simple to implement.

Cons:

- Cannot prevent concurrent logic errors by themselves.

- Violations caught only at commit.

Use cases: Always for data validation, combined with locking for critical updates.

#Isolation Levels and Locks

Postgres isolation levels affect how locks behave:

| Isolation Level | Behavior with locks |

|-----------------|------------------|

| READ COMMITTED | Each query sees only committed data. Locks apply per query. |

| REPEATABLE READ | Queries see the same snapshot. FOR UPDATE prevents others from updating locked rows until commit. |

| SERIALIZABLE | Most strict; transactions behave as if executed one at a time. |

Tip: Even with constraints, isolation levels and locks determine who blocks whom.

#Choosing the Right Mechanism

| Mechanism | Best For | Pros | Cons | |-----------|----------|------|------| | Pessimistic Lock | High contention | Safe, prevents conflicts | Blocks, deadlocks possible | | Optimistic Lock | Low contention | High concurrency | Needs retry logic | | DB Constraints | Always | Automatic integrity | Does not prevent race conditions |

Rule of Thumb:

- Always use constraints for validation.

- Use pessimistic locks for critical, highly-contended updates.

- Use optimistic locks when you expect rare conflicts.

#Extra Notes

FOR SHAREallows multiple readers but blocks updates.FOR KEY SHAREprotects foreign key relationships while still allowing updates to other columns.- Locks and constraints complement each other; constraints alone do not prevent race conditions.

#Real-World Example: IVR System

Imagine an IVR billing system where multiple agents can update pricing configuration:

CHECK(fixedPrice >= 0)→ ensures valid price.FOR UPDATE→ prevents two agents from overwriting each other’s updates.- Optimistic locking with

version→ allows multiple agents to work on different configurations safely, retrying if conflicts occur.

✅ Takeaways

- Locks = control who can access/modify data.

- Constraints = ensure data correctness.

- Pessimistic vs Optimistic = proactive vs reactive conflict handling.

- Combine mechanisms for robust, high-concurrency applications.